CREDITS

Psychology Today

By George Michelsen Foy

The Belgian comic characters turn 90 this week, prejudices intact.

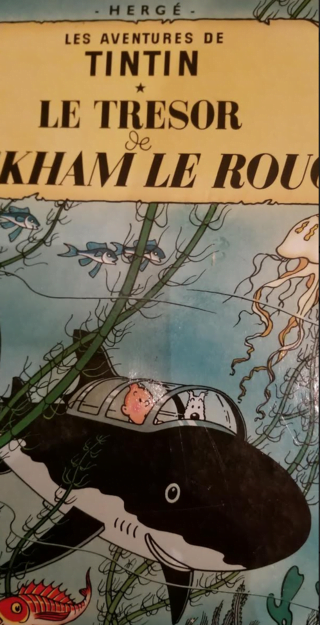

Tintin, the hero of two dozen children’s comic book adventures written and illustrated by the Belgian artist Hergé, turns 90 years old today. His birthday raises anew the question of how to deal with entertaining, popular stories conceived in times when imperialist, colonialist and individually racist attitudes were the Western norm and reflected in the behavior and attitudes of characters such as Tintin, in books for readers both young and old.

To mark Tintin’s birthday, Hergé’s publisher is bringing out a digitalized version of the first published book, Tintin in the Congo—a book that features bumbling Africans drawn with sausage-shaped lips, loincloths and spears, being helped out of witch-hurled curses and other situations by the kindly,

technology-savvy Belgian reporter.

Given the record of Belgians’ behavior in their former colony—during which, depending on which accounts you believe, between 1 million and 10 million Congolese died of overwork, abuse, torture and induced starvation under Belgian rule—the choice of Tintin in the Congo to celebrate the appearance of the young, cowlick-adorned, plus-fours-wearing investigative journalist seems insensitive at best. At worst, given the context, it appears to legitimize genocide.

“We really ask ourselves if it is the right moment,” a Belgium-based Congolese comic-book artist named Barly Baruti commented, referring to a recent resurgence in racist, right-wing groups in Europe.

It should also be noted that Tintin stories are massively, and ridiculously, male-oriented. The one female character who recurs in the series is Bianca Castafiore, a bombastic, overbearing and not particularly intelligent opera singer, notable for her huge breasts and girth and dreaded for her fondness for singing Gounod arias at a volume that literally breaks windows.

And yet.

And yet the Tintin stories are exciting, well-told, beautifully illustrated—and still popular with children of all genders today. They’re also very funny, filled with pratfalls, silly characters, and misadventures, many of them embarrassing to the hero.

And yet: Tintin’s behavior, while egregiously condescending, even somewhat contemptuous, of the intelligence and education of particular ethnic groups and Africans in particular, is actually quite enlightened by the standards of his time.

For one thing, from Congolese Africans to Chinese under Japanese rule to South American tribes to Native Americans in the US, Tintin always supports the underdog and tries to help him. It’s a paternalistic, condescending form of help of course, but given what was happening in real life to those ethnicities in the ’20s, ’30s and ’40s, it sure beats much of the competition.

I should also note that the two groups of people Hergé almost invariably depicts as despicable are the technologically-savvy Japanese (especially in China)—and Americans, especially American businessmen.

It’s a certainty that, even if one were to ignore the racism and sexism built into these stories, Tintin would never clear even the milder hurdles of Political Correctness. His best friend Captain Haddock, for example, is a raving and incorrigible alcoholic. Haddock’s butler, Nestor, has no life other than domestic servitude. Tintin’s dog, Snowy (Milou in French—as a Franco-American, I grew up on the original versions), regularly if accidentally gets plastered on whisky and other forms of booze. Recurring jokes surround the deafness of Professor Calculus, aka Professeur Tourneso

The controversy surrounding Tintin mirrors debate over a slew of other books written before our supposedly more enlightened times. Joseph Conrad, for example, set Heart of Darkness largely in the Congo, portraying Africans as savage, inept and so morally deficient that they dragged down even the supposedly “civilized” Europeans who ruled them. Ernest Hemingway used the N-word in referring to African-Americans and denigrated Jews through characters such as Cohn in The Sun Also Rises. Men who abuse women or at the very least treat them with condescension permeate novels written before the 1960s, and even after.

So should we ban Tintin, Conrad, Hemingway? Should our kids not read the Little House on the Prairie series because some of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s white characters espoused the negative stereotypes of Native Americans prevalent at the time, which led, in one recent instance, to the Wilder name being posthumously stripped from a children’s book award?

To go down that route would have several important negative effects. It would logically entail censoring the vast majority of world literature. It would empower authorities of various stripes, quite likely unelected, to ban books based on cultural values popular at the time but apt to change thereafter. And it would create yet another reason for people already addicted to the hypnotic, often socially deleterious blandishments of screen culture, to avoid the more thoughtful (and structurally less manipulative) pleasures of reading.

And yet—

It’s also important that kids reading Tintin, or high school students reading Hemingway, or adult readers moved by a Conrad tale set in the Far East, not absorb by osmosis the racist, or sexist, or homophobic values ingrained in the characters they follow.

We need to find a way to keep these books around, while also signaling that they carry cultural messages harmful to various genders or groups of people; messages which should be, not ignored, but discounted on rational, ethical and humanistic grounds.

It wouldn’t be so difficult. Novels such as Hemingway’s could be graded from A to F, like a term paper, based on the amount and power of socially harmful attitudes imbuing characters or narrative in the book, with the grade clearly marked on cover or flyleaf. No bureaucracy would be necessary to do this; local librarians and schoolteachers could grade such books as needed, and explain the reasons for a given grade on an ad hoc basis. Excesses in one direction or another would be dealt with normally, in school-board meetings or via the local press. The legal default position guaranteeing the freedom of free speech, in this case the freedom to read and write what one chooses, exists and must be maintained: namely, books cannot and must not be banned unless they pose a clear and present danger to civil society, such as calling for substantive acts of violence,

The crucial corollary would be that good books would not end up being forbidden or burned, and kids could laugh at Snowy’s antics, and adults be moved by Jake Barnes’ predicament, while taking with the proverbial grain of salt the outdated, inhumane values implied elsewhere in their pages.