CREDITS

Everyday Health

By Madeline R. Vann, MPH

Learning about mental health treatments we now know don’t work provides an important frame of reference for modern methods.

From Darkness Emerge New Treatments

Evidence abounds of inhumane treatment of the mentally ill throughout history. And though it’s easy to judge early interventions harshly, taking a look back can help us keep an evolving field in perspective. “I think that it is likely that in each generation, new views of the causes and mechanisms of psychiatric illnesses will emerge, and these ideas will lead to the testing of new treatments,” said John H. Krystal, MD, chairman of psychiatry and a professor of neurobiology at the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven.

Moral Treatment: Respectful of the Mentally Ill

In the 18th century, some believed that mental illness was a moral issue that could be treated through humane care and instilling moral discipline. Strategies included hospitalization, isolation, and discussion about an individual’s wrong beliefs. “Despite its limitations, its respectful treatment of people with mental illness and its efforts to meet the basic needs of these people, albeit through asylums, had a transformative impact in Western Europe,” said Dr. Krystal, who wrote an article, “Psychiatric Disorders: Diagnosis to Therapy,” in the March 2014 issue of Cell. Much of modern psychiatry has roots in this moral approach.

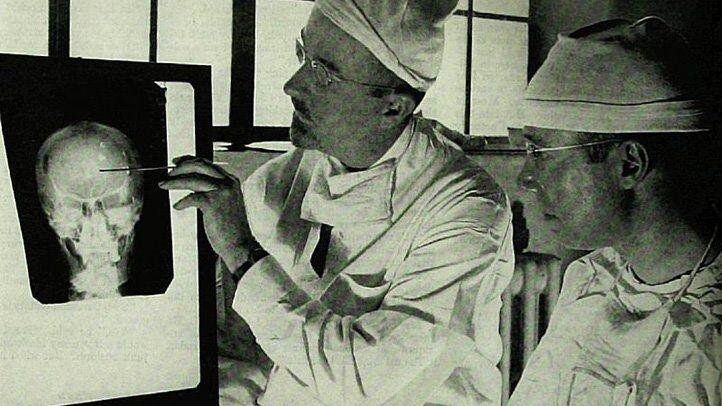

Lobotomy: Disrupting Brain Circuits

“Dr. Walter Freeman, left, and Dr. James W. Watts study an X ray before a psychosurgical operation. Psychosurgery is cutting into the brain to form new patterns and rid a patient of delusions, obsessions, nervous tensions and the like.

One of the few psychiatric treatments to receive a Nobel Prize, the lobotomy is also one that is now used infrequently. “Lobotomy was the first psychiatry treatment designed to alleviate suffering by disrupting brain circuits that might cause symptoms,” Krystal said. Experts soon realized, though, that the procedure wasn’t effective enough to justify its risks.

Lobotomies were a clear demonstration that mental illness treatments should be thoroughly tested before being widely used. But they did lead mental health professionals to research the connections between neurological signaling and mental illness. In appropriate patients, deep brain stimulation (DBS) and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) are used successfully, such as DBS for severe OCD and ECT for severe mania and severe or treatment-resistant depression.

Bleeding, Vomiting, and Purging: Fixing ‘Humors’

The Ancient Greek physician Claudius Galen believed that almost all ills originated in out-of-balance humors, or substances, in the body. In the 1600s, English physician Thomas Willis (pictured here) adapted this approach to mental disorders, arguing that an internal biochemical relationship was behind mental disorders. Bleeding, purging, and even vomiting were thought to help correct those imbalances and help heal physical and mental illness.

Trephination: Holes in Your Head

Perhaps one of the earliest forms of treatment for mental illness, trephination, also called trepanation, involved opening a hole in the skull using an auger, bore, or even a saw. By some estimates, this treatment began 7,000 years ago. Although no diagnostic manual exists from that time, experts guess that this procedure to remove a small section of skull might have been aimed at relieving headaches, mental illness, or presumed demonic possession. Nowadays a small hole may be made in the skull to treat bleeding between the inside of the skull and the surface of the brain that usually results from a head trauma or injury.

Mystic Rituals: Exorcism and Prayer

Due to a misunderstanding of the biological underpinnings of mental illness, signs of mood disorders, schizophrenia, and other mental woes have been viewed as signs of demonic possession in some cultures. As a result, mystic rituals such as exorcisms, prayer, and other religious ceremonies were sometimes used in an effort to relieve individuals and their family and community of the suffering caused by these disorders.

Physical Therapies: Ice and Restraints

A female patient, who is restrained in a straightjacket, sits alone on a bench in a mental institution, Youngstown, Ohio, 1946.

Moral treatment was the overarching therapeutic foundation for the 18th century. But even at that time, physicians had not fully separated mental and physical illness from each other. As a result, some of the treatments in those days were purely physical approaches to ending mental disorders and their symptoms. These included ice water baths, physical restraints (pictured here), and isolation.

Insulin Coma Therapy: Rewiring the Brain

Patient receiving insulin shock therapy treatment in mental hospital, which causes a coma condition in this patient.

Deliberately creating a low blood sugar coma gained attention in the 1930s as a tool for treating mental illness because it was believed that dramatically changing insulin levels altered wiring in the brain. This treatment lasted for several more decades, with many practitioners swearing by the purported positive results for patients who went through this treatment. The comas lasted for one to four hours, and the treatment faded from use during the 1960s.

Metrazol Therapy: Precursor to ECT

Bergonic chair for giving general electric treatment for psychological effect, in psycho-neurotic cases. World War 1 era.

As the understanding of mental illness evolved, some practitioners came to believe that seizures from such conditions as epilepsy and mental illness (including schizophrenia) could not exist together. So seizures were deliberately induced using medications like the stimulant metrazol (withdrawn from use by the FDA in 1982) to try to reduce mental illness. These seizures were not effective, nor were the outcomes of the treatments. (Researchers later realized that epilepsy and schizophrenia are not mutually exclusive.) This field of seizure-related therapies later led to the more effective study of electric shocks and ECT.

Fever Therapy: One Disease to Cure Another

The Ancient Greeks had observed that a period of fever sometimes cured people of other symptoms, but it wasn’t until the late 1800s that fevers were induced to try to treat mental illness. Austrian psychiatrist Julius Wagner-Jauregg (pictured here giving a lecture to students) infected a syphilis patient with malaria and the resulting fever cured the patient of the psychosis caused by his syphilis. Other diseases have been used to trigger brief fevers for the treatment of mental illness, according to an article in the June 2013 issue of The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine.

Asylums: Isolating the Patient

Asylums were places where people with mental disorders could be placed, allegedly for treatment, but also often to remove them from the view of their families and communities. Overcrowding in these institutions led to concern about the quality of care for institutionalized people and increased awareness of the rights of people with mental disorders. Even today, people with mental illness might experience periods of inpatient treatment reminiscent of the care given in asylums, but society exerts much greater regulatory control over the quality of care patients get in these institutions.